Understanding How Dimensionality Shapes Jet Stability in CFD

Published on: November 29, 2025

Introduction

One of the most consequential choices in any Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) workflow is dimensionality. It often feels like a purely pragmatic decision: use 2D to save computational cost, and switch to 3D only when necessary. However, my work on mixed convection, jet stability, and Floating Catalyst Chemical Vapor Deposition (FCCVD) reactors has highlighted that dimensionality does more than change the domain size—it fundamentally reshapes the physics.

When we reduce a model from 3D to 2D, we do not simply take a slice of the reality. We modify the mathematical operator governing the flow. By enforcing symmetry or suppressing velocity components, we remove specific derivatives and eliminate entire families of instability pathways.

This post outlines the mathematical and physical differences between 2D planar, 2D axisymmetric, and full 3D models. It explains why these choices are critical for asymmetric jets and buoyancy-driven flows.

Key Takeaways

- Dimensionality is a filter: Reducing dimensions removes terms from the Navier–Stokes equations, effectively “turning off” specific physical mechanisms.

- Axisymmetric 2D ($m=0$): Excellent for mean flows but artificially suppresses helical instabilities and azimuthal drift.

- Planar 2D: Allows for symmetry breaking (e.g., jet deflection) but lacks the vortex stretching mechanism required for turbulence cascades.

- 3D: The only domain that captures the full spectrum of azimuthal modes ($m \ge 1$) required for plume drift and helical flapping.

Governing Equations and the Dimensional Filter

Fluid motion is governed by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. To understand what dimensionality removes, we must first look at the full equations.

Continuity (Conservation of Mass)

\[\nabla \cdot \mathbf{u} = 0\]Momentum (Conservation of Momentum)

\[\rho\left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{u}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u}\right) = -\nabla p + \mu\nabla^2 \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{f}_b \, .\]Here, $\mathbf{u}$ is the velocity vector, $p$ is pressure, $\rho$ is density, $\mu$ is dynamic viscosity, and $\mathbf{f}_b$ represents body forces (such as gravity/buoyancy).

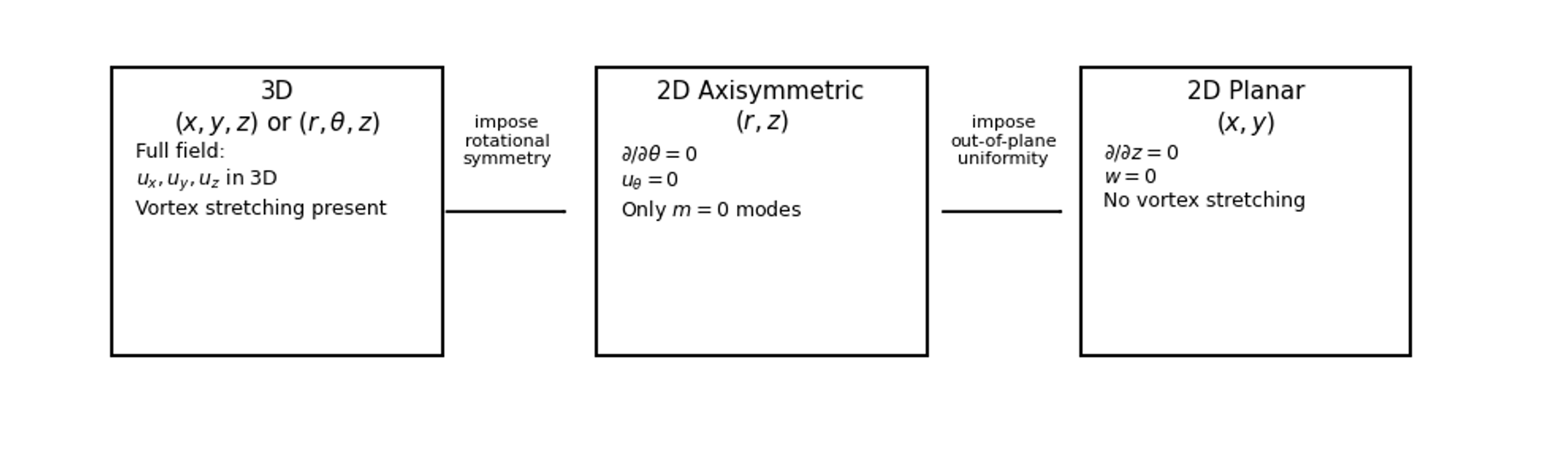

When we apply dimensional assumptions—such as setting $\partial/\partial z = 0$ (planar) or $\partial/\partial \theta = 0$ (axisymmetric)—we modify the differential operators. I visualize this as a filter applied to the Navier–Stokes operator: it passes certain physical behaviors while blocking others.

3D: The Full Physics and the Full Instability Spectrum

Figure 1. Dimensionality filtering applied to the Navier–Stokes equations.

In the full 3D formalism using cylindrical coordinates $(r, \theta, z)$, the velocity field is $\mathbf{u} = (u_r, u_\theta, u_z)$. The continuity equation includes gradients in all three directions:

\[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial (r u_r)}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial u_\theta}{\partial \theta} + \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial z} = 0 \, .\]The critical feature of 3D flows is the presence of the vortex stretching term in the vorticity transport equation:

\[(\boldsymbol{\omega}\cdot\nabla)\mathbf{u}\]where $\boldsymbol{\omega} = \nabla \times \mathbf{u}$ is the vorticity. This term is responsible for stretching and tilting vortex tubes, transferring energy from large scales to small scales. It is the engine of the classical turbulence cascade.

Furthermore, the 3D stability spectrum contains all azimuthal modes:

\[m = 0,\,1,\,2,\,\dots\]This allows for:

- Helical instabilities ($m=1$ mode).

- Jet flapping and meandering.

- Azimuthal drift of buoyant plumes.

Consequently, only 3D simulations can capture the “sinuous” or helical instabilities common in high-Reynolds-number jets.

Axisymmetric 2D: The $m=0$ World

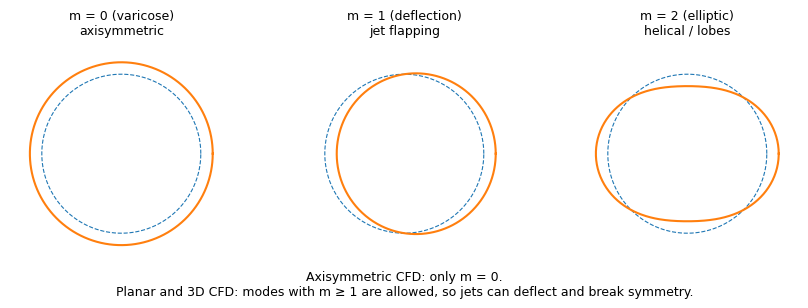

Figure 2. Axisymmetric modeling retains only $m=0$ modes.

Axisymmetry is a powerful simplification for pipes and round jets, but it comes with a strict constraint:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}=0, \qquad u_\theta = 0 \, .\]Mathematically, this restricts solutions to the $m=0$ azimuthal mode. Any perturbation of the form $\tilde{u}(r,z)e^{im\theta}$ is admissible only if $m=0$. The continuity equation reduces to:

\[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial (r u_r)}{\partial r} + \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial z} = 0 \, .\]Expert Note: The operator $L_{\text{axi}}$ is essentially the $m=0$ subspace of the full operator.

Because of this, axisymmetric CFD cannot represent:

- Helical motion ($m=1$).

- Lateral jet flapping.

- Buoyancy-induced azimuthal drift.

Axisymmetric models are excellent for predicting time-averaged mean flows, but they will fail to capture asymmetric physics if the real flow undergoes symmetry breaking.

Planar 2D: Limited Physics, But Free Symmetry Breaking

Planar simulations assume the flow is invariant in the third dimension (effectively an infinite slot or sheet). The constraints are:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial z}=0,\qquad w=0 \, .\]Continuity becomes:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial v}{\partial y} = 0 \, .\]In planar 2D, vorticity becomes a scalar, $\omega = \partial v/\partial x - \partial u/\partial y$. The transport equation simplifies significantly:

\[\frac{D\omega}{Dt} = \nu\nabla^2\omega \, .\]Crucially, the vortex stretching term vanishes:

\[(\boldsymbol{\omega}\cdot\nabla)\mathbf{u} = 0 \, .\]This means planar flows cannot generate the 3D energy cascade found in real turbulence.

However, unlike axisymmetric models, planar models can break symmetry within the plane. A centered jet in a planar domain is allowed to deflect left or right, a phenomenon critical for studying attachment instabilities.

The Pitchfork Bifurcation: Why 2D Jets Pick a Side

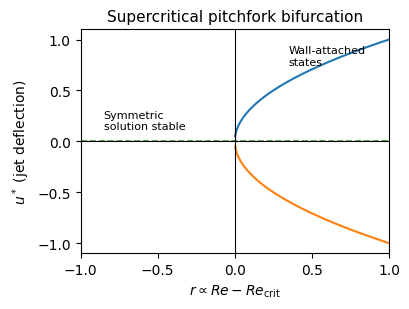

Figure 3. Supercritical pitchfork bifurcation for jet deflection.

The lateral deflection of a jet (often associated with the Coandă effect) is a classic nonlinear dynamics problem. Near the critical Reynolds number ($Re_{\mathrm{crit}}$), the jet’s lateral displacement $u(t)$ can be described by the normal form of a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation:

\[\frac{du}{dt} = r u - u^3 \, ,\]where $r$ is the control parameter proportional to $Re - Re_{\mathrm{crit}}$.

The steady states ($du/dt = 0$) are:

- $u^* = 0$ (The centered jet)

- $u^* = \pm\sqrt{r}$ (The asymmetric, deflected jets)

Stability is determined by the Jacobian $\lambda = r - 3u^2$:

- For $r < 0$ (low Re), the centered solution ($u=0$) is stable.

- For $r > 0$ (high Re), the centered solution becomes unstable, and the flow settles into one of the two asymmetric states ($u = \pm\sqrt{r}$).

This deflection is a physical result of the equations, not a numerical artifact. While numerical noise may trigger the transition, the stable states are mathematically inherent to the planar Navier–Stokes operator.

Application: FCCVD and Buoyancy

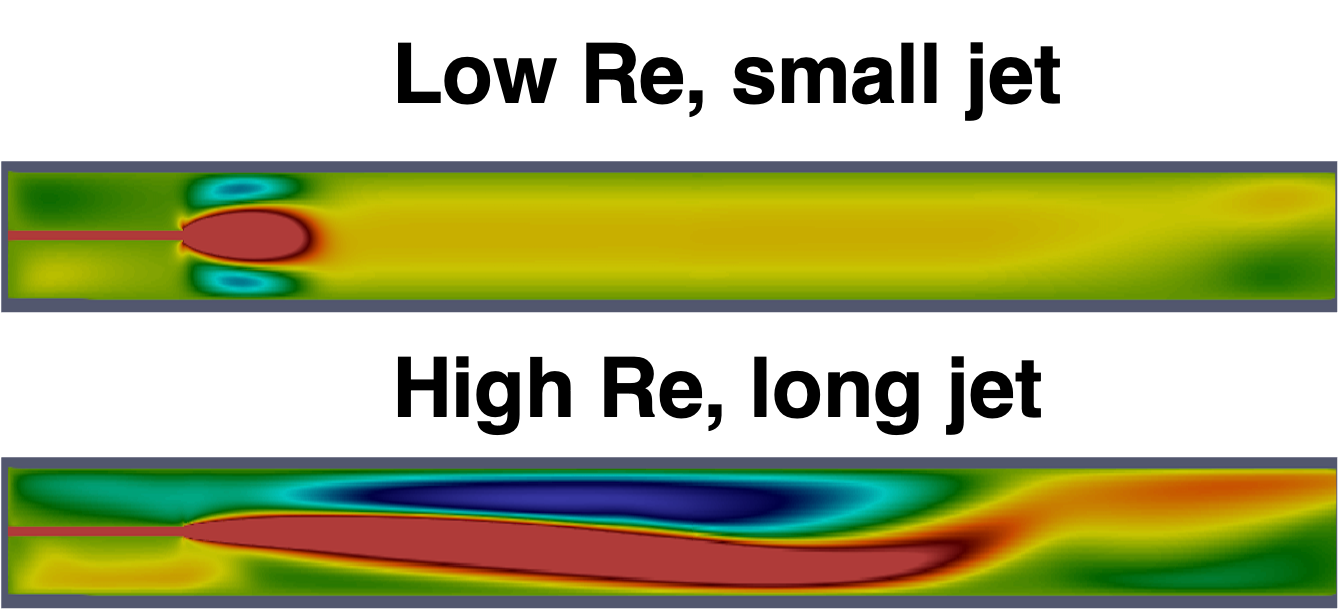

These dimensional constraints are particularly relevant for Floating Catalyst Chemical Vapor Deposition (FCCVD) reactors, which operate under extreme thermal gradients:

\[\Delta T \sim 800 - 1200\ \mathrm{K} \, .\]The driving force for convection is characterized by the Rayleigh number:

\[Ra = \frac{g\beta \Delta T\, L^3}{\nu\alpha} \, ,\]where $\beta$ is the thermal expansion coefficient and $\alpha$ is thermal diffusivity. In FCCVD, $Ra$ is typically large ($Ra \gg 10^4$), leading to complex mixed convection.

Buoyancy naturally introduces azimuthal perturbations of the form:

\[\tilde{u}(r,z)e^{im\theta},\qquad m=1,2,\dots\]- Axisymmetric simulations force these terms to zero ($m=0$), effectively suppressing plume drift.

- Planar simulations can show symmetry breaking but lack the correct 3D topology of a plume.

- 3D simulations capture the full behavior, including asymmetric recirculation and lateral catalyst migration.

Below is an example from a horizontal DI-FCCVD reactor.

Figure 4. Buoyancy-driven mixed convection in a horizontal FCCVD reactor (adapted from Junnarkar et al., Carbon 2025).

The large plume drift and asymmetric recirculation shown above correspond to modes where $m \ge 1$. These features require 3D modeling to be predicted accurately.

Closing Thoughts

Dimensionality is not just a computational setting; it is a physical assumption.

| Model | Removed Terms | Missing Physics |

|---|---|---|

| Axisymmetric | $\partial_\theta, u_\theta$ | Helical modes ($m=1$), lateral drift. |

| Planar | $\partial_z, w$ | Vortex stretching, 3D turbulent cascade. |

| 3D | None | None. |

2D models remain extremely useful for parameter sweeps and stability analysis, provided their limitations are understood. However, when the physics involves symmetry breaking, helical flapping, or strong buoyant plumes, we must accept the cost of 3D simulation to capture the correct instability spectrum.

References

- Effects of 2D Planar, Axisymmetric, and 3D Simulations on Jet Behavior and Stability.

- Hou, G. et al. Carbon nanotube reactor: Ferrocene decomposition…

- Fearn, Mullin, Cliffe. Nonlinear flow phenomena in a symmetric sudden expansion.

- Strogatz, S. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos.

- Anderson, J. D. Computational Fluid Dynamics.

- Additional unpublished FCCVD simulations.

- Private communication, Pasquali Research Group.